Creative Commons licenses allow you to retain your copyright while inviting certain other uses of your work, which could ultimately spread your work much farther than you could do on your own.

Perhaps you’ve seen one of the six Creative Commons (CC) logos and wondered, “What does that mark mean?” Or perhaps you’ve wanted to share your work more broadly but were scared of losing control of it? Or maybe you’ve heard of others who are successful at getting their work “out there” and want to do the same? We know this chapter is for you!

“Open licensing” refers to a number of different frameworks, but in this chapter we’ll be focusing on one of the most common and most successful licenses, Creative Commons (CC) licenses. Understanding how CC licenses work and how to apply them to your own creative outputs can help spread your impact and scholarly reach much further than you could on your own.

But before we dig into CC, you first have to understand...

In order to understand Creative Commons licenses, you need a basic understanding of copyright. Really. You do.

Copyright is the intellectual property law that protects creative works from theft and misuse. Copyright is a legal claim to your work and the work of others. By default, you have copyrights to any original creative work as soon as you express it in a tangible form. So the thoughts you have about how to solve your latest research problem are not protected by copyright. But as soon as you write those thoughts down, publish them, paint them, or photograph them (or do an interpretive dance) they are considered expressed in a tangible form and are given copyright protection.

Typical copyright can be thought of as:

Types of work protected by copyright include:

Types of work not protected by copyright include:

If you want to use someone else’s copyrighted work in any way, you must first get permission from them (ideally in written form). If you’ve ever tried to do this, you know how difficult or awkward it can be.

Tracking down someone who has a common name or who has various institution affiliations (some of which might be outdated) might lead you astray in a search for permission or “license” to use their work.

This doesn’t even take into account how difficult it can be to obtain a license (or permission) from someone who is no longer alive.

That’s right.

A person’s intellectual property is protected by copyright for at least 70 years after their death. If that fact helps or hinders you, you have Mickey Mouse to thank. And there are many exceptions.

In the fortunate case when a creator transfers their intellectual property rights at the time of their death, you are still left with the task of tracing the inheritance of those permissions.

And really. Do you want to go through all that? Do you want others to go through all that to find YOUR work?

Copyright is automatically applied to a work after its tangible expression, so it might not even be your intent to keep your work in such a locked down state. Yet that just happens to be the way U.S. intellectual property law works at the moment.

But say you are able to obtain a license (permission) to use someone else’s work. What then? How do you know what you’re really able to do? What permissions do you have?

If you did receive these permissions, how robust are their terms? Do they have a chance of holding up in court?

Creative Commons is a non-profit organization with a legal framework that enables creators to publish works while explicitly granting permission for those works to be used in ways that would typically be prohibited by copyright.

Creative Commons licenses are written to be legally enforceable around the world, and have been enforced in court in various jurisdictions. To CC's knowledge, the licenses have never been held unenforceable or invalid. Their licenses allow creators to grant standing permissions to anyone who seeks to use their work. This means, “you already have some permission” to use the work. There is no need to search out the creator in order to use it.

“But what permissions?” you may ask. What does “some permission” mean? Will my work get stolen or plagiarized? First, read on. Second, in an online digital world plagiarism is easier than ever to find.

You decide upon permissible uses of your work, and Creative Commons takes care of the license in both plain and legal terms. Creative Commons licenses are made up of four components that are grouped into six licenses that make up a spectrum of permissiveness.

Attribution: All CC licenses require that those who use a work give credit to its creator in the way requested by that creator, but not in a way that suggests the creator endorses the user or their use. If you want to use a work without crediting the creator, you must first get permission to do so.

ShareAlike: You will let others copy, distribute, display, perform, and modify your work, as long as they distribute your modified work on the same terms. If they want to distribute modified works under other terms, they must get your permission first.

NoDerivatives: You will let others copy, distribute, display, and perform only original copies of your work. If they want to modify your work, they must get your permission first.

NonCommercial: You will let others copy, distribute, display, perform, and (unless you have chosen NoDerivatives) modify and use your work for any purpose other than for commercial purposes. If they want to use your work for commercial purposes, they must get your permission first.

Still with us? Because it gets easier from here, as long as you understand the above.

These above components are then combined into six licenses listed here from most permissive (most open) to most restrictive (least open). You’ve likely seen the images above each explanation, right? But let’s get to understanding them.

Attribution (CC BY): Others may do anything they like with a CC BY work (including sell it for commercial purposes) as long as they attribute, or give credit to, its creator. For example, the OU Impact Challenge is possible, because the original creator licensed her work CC BY.

Attribution – ShareAlike (CC BY-SA): Others may do anything they like with a CC BY-SA work as long as they attribute its creator and share any derivative works under the same license, CC BY-SA. This license (along with the CC BY licence above) perpetuates sharing.

Attribution – NoDerivatives (CC BY-ND): People who use your CC BY-ND works are limited to only redistributing your original work. They cannot make derivatives of your work, which means they cannot build upon your work. But, of course, under this license, others are required to attribute you as the creator of the work.

Attribution – NonCommercial (CC BY-NC): Anyone can do anything they like with your work, as long as they do not profit from it. Attributing you – as the creator – is also required.

Attribution – NonCommercial – ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA): Others may do anything they like with a CC BY-NC-SA work as long as they do not profit from it and they share any derivatives under the same license as the original, CC BY-NC-SA. Attributing the work’s creator is also required. We can tell you from experience, this license can be complicated. It sounds reasonable until you consider all the ramifications.

Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivatives (CC BY-NC-ND): Others may do anything they like with CC BY-NC-ND works as long as they do not profit from or make derivatives of the original work. Attributing the work’s creator is also required. In essence, this license only allows users to share copies of the original work but not for profit. But this is more than copyright does!

Some people claim that CC BY licenses are the only truly open licenses, and they cast the other CC licences in an unfavorable light. We do prefer works to be distributed under the most open license possible, but we also firmly believe that each of these licenses have appropriate uses and places in the commons.

If you’re choosing to use a CC license, you need to choose one that best suits your work and your personal comfort.

Anecdotally, we have seen more restrictive CC licenses acting as a gateway to less restrictive licenses.

If you’re using a CC license for the first time you might prefer to use those that more closely parallel the all rights reserved nature of copyright. After a while you might be more comfortable moving up the scale towards the less restrictive licenses after experiencing the benefits of sharing your work openly.

In any case – it’s your work; you are the author, and you are the only one who can decide what is best for you and your work.

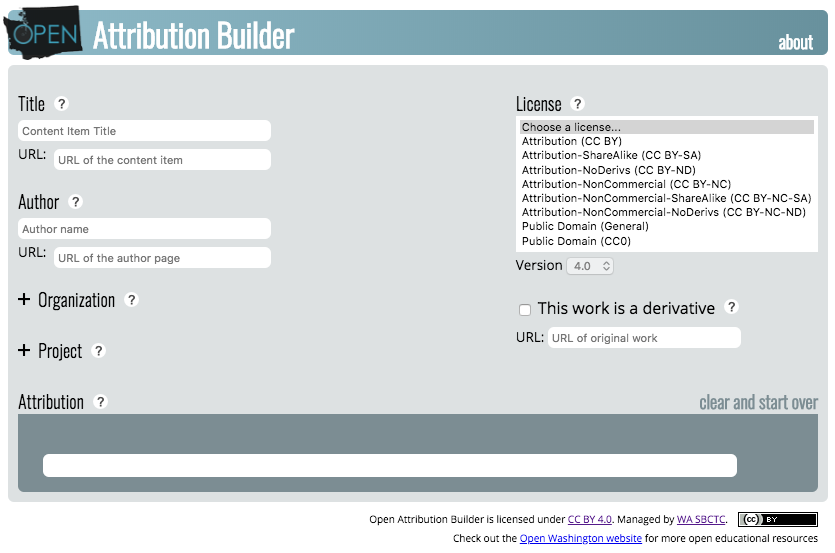

Because copyright is automatically applied to creative works, you must clearly declare that a work has a CC license. The Creative Commons website has a handy tool for helping you decide which license is best for your work, and it provides language that clearly declares that your work is protected by the terms of that license.

There is no mechanism by which to register a CC licensed work; simply include the license declaration in your work. How this is done will vary depending on the medium in which you publish your work. CC licenses are usually found in the footer of web pages and on the copyright page of written works.

This is where we want to point out the license in formation at the bottom of this very page. Yes, all content in the OU Impact Challenge is openly licensed! This means that others can use this work, build upon this work, and release it ways we may not have even thought of.

Furthermore, we were able to create this Impact Challenge by building on the original work, which was openly licensed (see the licensing terms on page 3). We would not have been able to do this as easily if the original content had been under traditional copyright.

When others use your Creative Commons licensed work they are required to provide attribution (give credit), and there is a proper way to do that. We’re used to citations, bibliographies, and reference lists. Attribution is a bit different though.

Rest assured, there are lots of people looking out to protect your work from misuse. For example, the good people at Open Washington created this attribution builder. This helps others attribute your works.

And a bonus! When you want to find openly available works that you can use yourself we still recommend that you use an attribution builder to make sure that you are properly giving credit.

So now that you understand the basics of Creative Commons licenses, what about the why? Why is openly licensing your work important? Well, that’s easy…

For one, openly sharing academic works has been proven to increase the number of citations they receive and spurs a cycle of reciprocity that has the potential to accelerate the pace of research.

Next, the benefits of openly licensing educational resources are twofold. For one, students stand to benefit from using openly licensed resources, as there is typically no cost associated with them. The cost barrier of education is significant and is one of the primary ways an instructor can influence students’ access to education.

Secondly, instructors stand to benefit from using open educational resources because they are able to modify, correct, and adapt them to better fit their specific needs. Most would modify a textbook they currently use given the opportunity. Open educational resources provide just that opportunity.

We have no doubt you’ve generated intellectual property that others stand to benefit by having unrestricted access to. These might range from course notes, to articles, syllabi, video lectures, books, chapters, slide decks, even photos on your phone. This week’s activity is to contribute something to the commons. You can do this in a number of ways,

Be sure to choose one of the CC licenses before uploading your work to one of the above platforms. And then let your colleagues know that you’ve contributed resources that might be useful to them by tweeting links to your published resources or by posting the same links to your discipline’s listservs.

Start a conversation with your Liaison Librarian to learn how you can publish your next article in an open access journal or make your existing articles more openly available.

This guide is based on the "30-Day Impact Challenge" by Stacy Konkiel and used here under a CC BY 4.0 International License and the OU Impact Challenge which is also licensed CC BY 4.0. Many thanks to those authors for creating and sharing these materials.